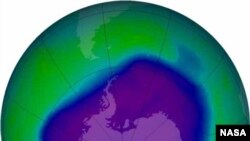

In 1985, research scientists in Antarctica discovered a thinning of the layer of ozone gas above the earth that protects life here from the sun's ultraviolet rays. Man-made chemicals released into the atmosphere were causing a hole in the ozone that if not controlled could have resulted in an environmental disaster. An international accord signed the next year banned the chemicals involved and phased out their use. Now the United States, Mexico and Canada are teaming up to use the accord to fight another environmental threat linked to human activity: global climate change.

At a conference in Switzerland next month, the three North American neighbors will raise a proposal to add hydrofluorocarbons, or HFCs, to the list of chemicals controlled by the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. Their use as a refrigerant has increased as makers of air conditioners and kitchen refrigerators look to replace the chlorofluorocarbons and other substances being phased out by the Montreal Protocol. Scientists in the U.S. believe that phasing out HFCs would produce environmental benefits equal to removing the greenhouse gas emissions of 420 million cars each year through 2050.

Every nation in the world has ratified the Montreal Protocol, so Canadian, Mexican and American officials see it as a good vehicle to address environmental threats beyond a thinning of the ozone layer. Without international restrictions on this potent class of greenhouse gases, HFC use could grow substantially, thanks to increased demand for refrigeration and air-conditioning in the developing world.

Reducing the use of these chemicals will help slow climate change and curb potential adverse health effects not just in North America, but across the globe.

Teaming Up To Fight Climate Change

The U.S., Mexico and Canada are teaming up to fight another environmental threat linked to human activity: global climate change.